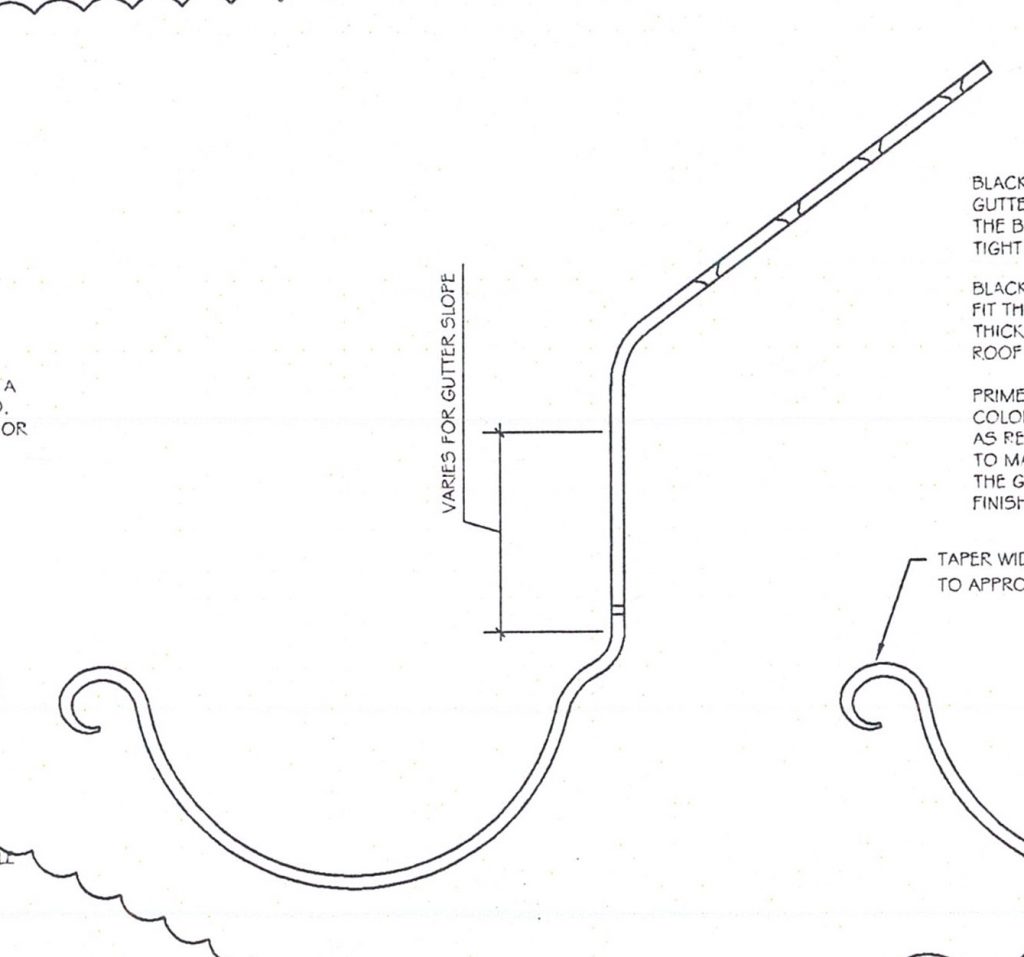

On the 31st of August 2022 we received our final shipment of shingles for the Stone House roof. This delivery closed a chapter in the story of the Stone House Restoration Project that began in the early 1990s with the initial phase of the planning to restore the Stone House. At that time our founding board was aware of the fact that one of the most common roofs in Newtown/Stephensburg during the eighteenth century on through the third quarter of the nineteenth century was the side-lap wood shingle roof. This was clearly evident in the earliest historical photographs of buildings on Main Street and in surviving evidence in the historic structures themselves. Early searches to find craftsmen capable of making shingles like these in the correct historic fashion proved unfruitful. The people who recover and cultivate the manufacturing technological skills of the pre-Industrial Revolution era are hard to find. On top of this is the added challenge of keeping a workforce trained in the skills associated with these largely obsolete technologies. We are grateful to Mr. David Dauerty (pictured below) for persevering, despite a number of personal and professional challenges, to complete our order for the 4,900 long biaxially tapered side-lap shingles that we needed to cover both sides of the Stone House’s roof structure. We signed the contract with Mr. Dauerty in November of 2018. It is good to finally be in possession of these handmade roofing materials.

Our next step is their installation over the log side of the structure. In large measure, this will be a repeat of what we accomplished in 2021 with the roof over the stone side of the house, except we will not need to deal with tucking them under the weatherboards of an abutting exterior wall. We will again be engaging the services of Mr. David Logan’s Vintage Inc. out of Winchester, Virginia for the prep work and the painting of the shingles once they are installed. The installation of the shingles themselves will be done once again by Mr. Frank Stroik’s crew of The Country Homestead firm out of Middleburg, Pennsylvania. Mr. Stroik is currently hiring and training workers in preparation for our shingle installation project.

Once the last of the shingles are installed and painted, we will begin the next phase of the Stone House Restoration Project. While it will not be as dependent on pre-Industrial Revolution technologies, this next phase of the work will still be a challenge due to the complexity of the engineering it will require. As we have discussed in previous issues of this newsletter, the archeological evidence indicates that there was a porch on the rear of the stone side of the Stone House. The new porch that we plan to build will need to be designed and constructed in a historically sensitive fashion. It will also need to serve as a buttress to support the east wall of that stone side of the house, which leans out too much from the structure’s center of gravity. We have engaged the professional services of Main Street Architecture in Berryville, Virginia to assist us in this design work. But first, we are celebrating the arrival of our shingles!