We were hoping that by this time we would be able to report on the installation of our side-lap shingle roof. Unfortunately, the contractor who is making the 4,900 shingles by hand has run into problems with the wood supplied to him for the job. With shingle making the quality of the wood is critical. When warping and splitting of shingles happens, it leaves you with nothing but what our contractor calls “expensive firewood.” Our contractor is still working on getting the job done as soon as possible while we prepare the roof structure that will support them.

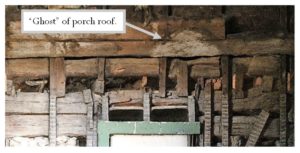

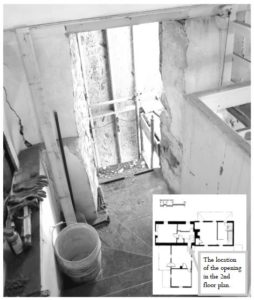

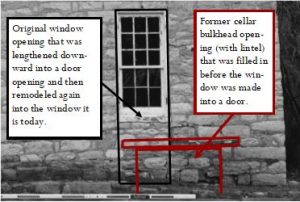

In the meantime there was one more discovery that we made in our forensic examination of the stone side of the structure that is worthy of our attention here. As our historic structure consultant, Mr. Doug Reed, removed plaster, wood trim, and framing from around the rear doorway in the east wall of the stone side of the house, he discovered clear signs that the opening in that wall had been altered from a window to a doorway. The evidence included the use of bricks to fill in gaps left where stones were removed as the opening was extended down to the floor level. (See photo below.)

Sandwiched in between the courses of infill bricks are wooden blocks that served as nailers for an earlier door frame to be mounted in this opening. These bricks and the wood nailer blocks have whitewash on them, as do the stones on the other side of this doorway opening. The whitewash is typical for the former exterior surfaces of the Stone House. As we have said previously, we have found whitewash on all the historical outer wall surfaces that were later covered or encapsulated. Because these whitewashed surfaces were protected from the elements they were preserved for us to study today.

This discovery of a window becoming a rear door means that the original design of the Stone House was not the way we had previously believed it to be. It did not have opposing front and rear doorways in the main room of the first floor. This was a bit odd. One of the most common features of Virginia’s Georgian vernacular architectural tradition is the use of ground-floor doorways that are situated in the front and rear of the structure. These doorways were typically positioned to line up, and make it possible to pass directly in a straight line through the house from one side to another. It is recognized by architectural historians that this allowed for better air circulation on hot summer days when a cross breeze through the building would be very welcome. The original rear window opposite the front door in the stone side of the Stone House no doubt performed a similar service, except with smaller volumes of air.

So the question this discovery raises is where was the back door in the original stone structure? The problem with this question is that its premise assumes that there had to be a back door in the original floor plan of the Stone House. Architectural historians who study late-medieval, and early-modern vernacular houses in Great Britain have found that small cottages of one or two rooms like the Stone House did not always have more than one entrance. In fact, the late Ronald W. Brunskill (1929-2015), one of the leading British academics who studied the historic vernacular architecture of his homeland, noted several examples of single-entry historic house types in his published works. Could it be possible that George Cabbage, the original builder of the Stone House, was following this custom that he knew from his homeland when he conceived of its floor plan? If so, it would not be the first time that a British immigrant to the American colonies built a house like they had previously known in their homeland.

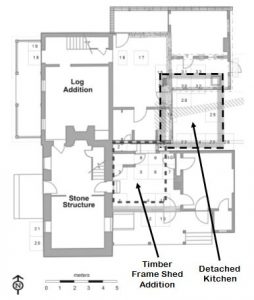

Our historic structure consultant, Mr. Reed, has also discovered a blocked doorway behind the wall on the east side of the ground-floor fireplaces and chimney stack. This disused doorway once allowed passage between the stone side of the house and its log addition. Mr. Reed believes that also it originally could have been a doorway leading to the exterior of the stone side of the house before the log addition was constructed. While this theory remains controversial, it could answer the question about where a back door of the Stone House was originally located.

Ultimately, these discoveries do not have any bearing on our restoration of the Stone House to its 1830 appearance. The rear window on the stone side of the house had already been turned into a door by then, and the doorway to the east of the ground-floor fireplaces was also already blocked off by that time. Even so, these discoveries are interesting and worthy of our attention.