In our last post we began to explain how the nails discovered in the dado panels of the first floor south room of the stone side of the house are helping us know when those panels were installed. We also discussed how dating the installation of those panels relates to the construction of the rear bulkhead entrance to the cellar. In this second post on this subject, we will address the other nail evidence that we have discovered and analyze what it might mean. To do this we will focus on the nails that were made with machine-cut shanks and mechanically stamped heads during the long period from the 1810s to circa 1900. (See figure 1 below.)

It can be very difficult to determine the manufacturing date of nails like this because they all can superficially appear to be very much alike. Despite their similarities in appearance, there are certain characteristics that distinguish the early cut nails with machine-stamped heads from the ones made later in the period. To begin to recognize the earliest cut nails with machine-stamped heads from later ones, readers need to understand the difference between wrought iron and steel. Today almost all nails are made with steel. Steel is primarily an alloy of the elements iron and carbon. Prior to the invention of the Bessemer process in the 1850s, the manufacture of steel was relatively time consuming, labor intensive, and more expensive. Thus, steel was used sparingly where it was needed. Nails were not made of steel until the late 1870s.

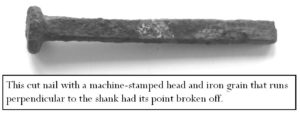

Wrought iron is an alloy of elemental iron with very little carbon in it. Its manufacturing process was less complicated than the way steel was made in that period. It involved heating and hammering or hot-rolling smelted iron. The principal difference between wrought iron and steel for our purpose here is that wrought iron has siliceous slag inclusions that are layered in such a way as to form what resembles grain in wood. Steel does not. This grain-like characteristic in wrought iron runs lengthwise through a bar, and these siliceous slag inclusions tend to cause weaknesses in the iron’s molecular bond where they are located. Bars intended for nail manufacture were sent to rolling and slitting mills to be made into plates before they were cut into nails. At first the plates from which cut nails were made were rolled and cut so that the grain ran perpendicular to the nail’s shank. This caused the earliest cut nails to sometimes break in half (instead of bending) where the siliceous slag inclusions caused inherent weaknesses in the nail. By the early 1820s the nail-manufacturing technology had improved. The plates that the best cut nails were made from were rolled so that the iron grain ran parallel to the nail’s shank. This made it possible to bend or clinch a cut nail of this type. By the early 1840s nail manufacturers stopped making cut nails with the iron grain running perpendicular to the nail’s shank, as they were too easily broken.

Along with the nail we discussed in our last issue, we found these two types of cut nails in the dado panels. The ones that were used to nail the dado panel to the wall were the type with iron grain running perpendicular to the shank. As expected, the tips of these nails were all broken off due to the weaknesses in their molecular bonds around the siliceous slag inclusions. These nails could not bend or be clinched without breaking. (See image below.)

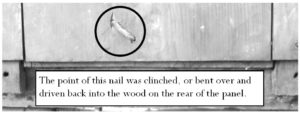

The other cut nails used in the dado panels are the type with their iron grain running parallel to their shank. In other words, these nails could bend without breaking. They were used to fasten the panel’s baseboard to the individual repurposed cabinet doors that were lined up side by side to make up the dado panel. They were driven through the baseboard and then clinched so their tips were bent over and driven into the wood. (See photo below.)

The presence of these three types of cut nails in this dado panel implies that the carpenter who hammered them in was working at a time when all three types of nails were still commonly in use. That time was around 1830, at the end of the period when the earliest cut nails were being replaced by the new cut nails that could be clinched like the nail pictured above.