Despite the anti-slavery sentiments of some of its most influential citizens, John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry Arsenal went too far for the majority of the town’s white citizens. The militia units of Frederick County responded to the alarm, and Newtown/Stephensburg supplied its complement of citizen soldiers to quell the potential uprising. When the Civil War finally broke out in 1861 the majority of Newtown’s young men of military age showed their loyalty to their state and joined the Confederate forces that were being organized. Fortunately for us, the Steele family of Newtown kept diaries during the period of this war. It is because of these diaries that we know many details of the war’s impact on the town. The Steele family’s oldest son was a young lieutenant named Nimrod Hunter Steele. “Nim” Steele grew up in Newtown before the Civil War. He served as a lieutenant in the Newtown Artillery, a prewar militia unit assigned to General Elzey’s 16th Brigade, Battery C, 3rd Virginia Division that was headquartered in Winchester. Lieutenant Steele and his artillery unit were engaged at the Battle of First Manassas or “Bull Run” in July of 1861. By October an epidemic of typhoid infected the camp where Lieutenant Steele was stationed. He contracted the disease and was eventually sent home to Newtown where he died 16 November 1861. His two younger brothers, Mager William Steele and Milton Boyd Steele, also served the Confederacy during the war. Mager served in the 48th Virginia Infantry from November 1862 until the end of the war. Milton enlisted with Company A of the First Virginia Cavalry on 1 September 1863 and prior to that had served as a wagon driver during the Gettysburg campaign. Both young men survived the war and went into business together, operating the Steele & Bro. Store that is today one of the exhibition buildings operated by the Newtown History Center.

Their youngest brother John Magill Steele (1853-1936) was too young to serve in the war but kept a diary with his sister Sara Eliza Steele beginning 19 January 1863 until 19 January 1864. Forty-one years after the war the fifty-three-year-old John M. Steele wrote down his memories of the Civil War with the help of this diary. In this memoir John M. Steele characterized the wartime situation of the town as being “between the lines.” Newtown became a no-mans-land for much of the war. It was close enough to suffer the effects and disruptions to daily life that came with the Federal troops’ occupation of Winchester and the surrounding region, but distant enough to return to limited Confederate control after nightfall. Fortunately for the town, most of the battles, skirmishes and engagements that took place in the vicinity of Newtown did not threaten the lives and property of the town’s residents.

One notable exception was on 24 May 1862 when Stonewall Jackson’s Confederate forces were advancing northward on the Valley Pike from Middletown. They had earlier defeated Union troops in Front Royal the previous day. Jackson’s men were hitting the rear columns of the retreating Federal forces as they reached Newtown. At Newtown General George H. Gordon (1825-1886) of the Second Massachusetts Infantry ordered the Federal troops under his command to make a stand and stop the Confederate advance. For the next hour or more there was skirmishing and continual artillery fire between the lines over and around the town. Gordon’s men were able to halt the advance of the Confederate forces long enough to ensure that no more Federal wagons were lost. Gordon left the town to Jackson’s forces, and both sides claimed a victory. Years later Inez Virginia Steele (1838-1902), the eldest surviving sister in the Steele family, recalled the events of that day when “the town changed possession six times” and the artillery battle raged. “Considering how thickly the shot and shell sometimes flew, it seems almost incredible that but two houses were struck by cannon balls.”

The other events that occurred during the last weeks of May 1864 and culminated on 1 June 1864 could have had devastating effects on the town for generations to come. On that first day of June Major Joseph K. Stearns of the 1st New York Cavalry came to Newtown with his men carrying orders to burn the town. It had all started over a week earlier on the evening of the 23rd of May, when partisan Confederate sympathizers from Maryland fired on a Federal wagon train from horseback as they rode away, shot one Union soldier and escaped. In the confusion that followed a number of the Federal troops unhitched their wagons, left them on the street in the town and rode the horses away to Winchester. In retaliation, and without knowing all the facts, Union General David Hunter (1802-1886) ordered Major Timothy Quinn of the 1st New York Cavalry to burn the houses from which the shots were fired as a warning to the citizens of Newtown not to attack any more Federal wagon trains. In turn Major Quinn burned at least three houses, including the Methodist parsonage and a brick house owned by a local entrepreneur slave trader. Ironically, Major Quinn burned the parsonage because one of the Federal wagons had been left on the street in front of the house by an African American man who had tried to move it to his own home but gave up on his plan before reaching his goal. It was also at this time that General Hunter issued a written proclamation saying that the he would order the burning of the town if any more of his soldiers and wagons were attacked.

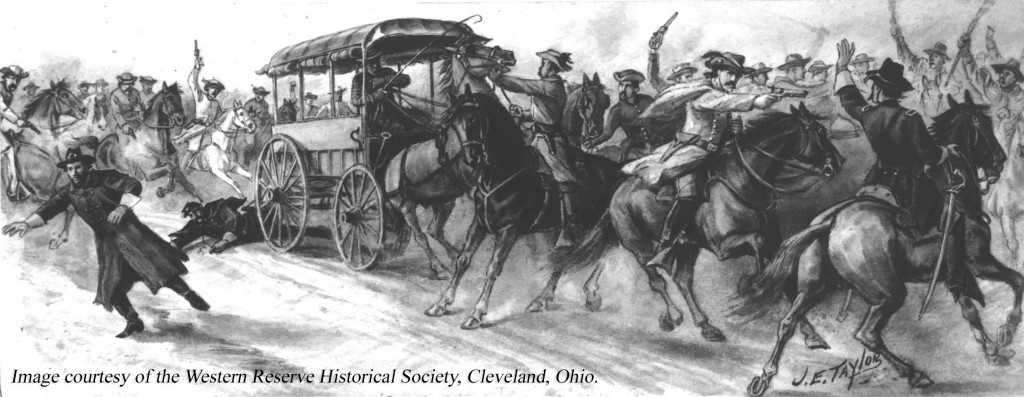

By the evening of the 29th the people of Newtown were the unfortunate bystanders once again when Confederate Colonel Harry Gilmor (1838-1883) and his partisan rangers attacked a Union wagon train guarded by 83 men of the 15th New York Cavalry at Stephens Run near the southern end of town. Despite the pleas of at least one resident, Eliza Kern Steele (1808-1882, the mother of the Steele family), Colonel Gilmor attacked the wagon train within the town boundaries. After it all was over, Colonel Gilmor and his men had killed three, wounded nine, taken the others as prisoners and burned most of the wagons at the southern end of the town. Colonel Gilmor then learned of General Hunter’s threat to burn the town if any more wagon trains were attacked. He was shocked but quickly wrote a note addressed to General Hunter. In this note he said he held thirty-five men and six officers, and Gilmor promised to hang all of them and send General Hunter their bodies if Hunter carried out his threat to burn the town. This note was then nailed to the door of a local store.

The morning of the following day Confederate Colonel John Singleton Mosby (1833-1916) and his men raided the rear guard of another Federal wagon train heading north on the Valley Turnpike just south of town. They killed two of the Federal soldiers and captured five others with their horses and equipment. One of the captured men was reportedly caught in the act of burning a barn south of town. Colonel Mosby’s men brought him to the town’s hotel (the building that today houses the Newtown History Center) and gave this prisoner some breakfast as his last meal. The prisoner was then taken to the burned ruins of the slave trader’s brick house east of town and shot against one of the remaining brick walls.

The first of June came with the residents of Newtown scrambling to save as many of their movable possessions as they could by hiding and burying them in their yards. When Major Stearns arrived in town to execute General Hunter’s burning orders, he and his men were met by the sight of old people, women and children standing in the doorways of their homes with expressions of despair and helplessness on their faces. Community leaders also met him, protesting the innocence of the townspeople. They disassociated themselves from the attacks by Gilmor and Mosby and spoke of the aid they had given to the wounded Federals in their homes. Compassion may have played a role in Major Stearns’ decision to disobey General Hunter’s orders. In exchange for not burning the town, Major Stearns required the people of Newtown to take the oath of allegiance to the Union. It is also possible that Colonel Gilmor’s note nailed to the door of that local store threatening to kill his Federal prisoners played an important role in Major Stearn’s decision. In any case, the town was spared and many of the old buildings that would have been burned by General Hunter’s men still stand today in Stephens City.

Throughout it all the African American community in Newtown and its suburb of Crossroads were both observers and participants in the local events of the war. With Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the efforts of Union troops to enforce it, slave owners in Newtown were forced to let go of the people they had held as property. The majority of these emancipated African Americans left the area along with a number of the free blacks that had lived in the town. Ironically, for those who stayed, the collapse of Confederate military power in the northern Shenandoah Valley after the Battle of Cedar Creek in October of 1864, did not signal the end of the difficulties associated with the war. During the winter months of 1864 –1865 Federal troops built a camp just north of Newtown in the area around Bartonsville and called it Camp Russell. In the course of building this winter camp the Federal troops dismantled the African American Methodist chapel with a few other structures in town and used the lumber and bricks to build their shelters. The demolition of this separate house of worship did not dampen the determination of the African American Methodists in Newtown. Fortunately for them there was in Winchester at that time, a former slave named Robert Orrick (ca. 1827-1902) who owned a successful livery stable business. Orrick was also a preacher and leader in the local African American Methodist community. With the financial help of Reverend Orrick, the African American Methodists of Newtown built a new house of worship and named it Orrick Chapel in honor of their benefactor. This chapel still stands today with modifications and is owned by the Stone House Foundation.