The firm of Steele & Bro. purchased the stone side of the Stone House duplex from Jacob and Mary Shryock on 17 January 1872 for $225. Of all the owners of this property perhaps none of them have had a more lasting influence on this building’s future than the firm of Steele & Bro. This is because the founder of the Stone House Foundation, Mildred Lee Grove, was a granddaughter of Milton Boyd Steele, the junior member of the Steele & Bro. partnership. Miss Grove reported that one of the reasons she purchased the property on 11 May 1940 was because she knew it had once belonged to her grandfather. It was also the place her grandmother Altha Watson Steele lived as a child for a short time at the beginning of the Civil War, after returning to Virginia from Hannibal, Missouri with her stepfather William Rosenberger and her mother Margaret Nisewanger Watson Rosenberger.

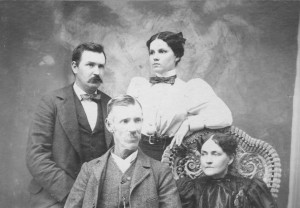

Mager W. Steele and Milton B. Steele were sole proprietors and partners that made up the firm of Steele & Bro. They were both sons of Mager Steele, Sr. (1788-1863), and Eliza Kern Steele (1808-1882). Mager Steele Sr. was the son of Thomas Steel (1750-1834), an immigrant from Belfast, Ireland who came to America around 1765 and eventually settled southeast of Stephensburg in the area where Wise Mill Lane crosses Stephens Run. The first of the nine children born to Mager, Sr. and Eliza were girls. We know very little about Ann Margaret Steele (1836-1863) who may have been an invalid, and died during the Civil War a month after her father passed away. Inez Virginia Steele (1838-1912), the second oldest daughter, never married and was the author of Early Days and Methodism in Stephens City, Virginia, published originally in 1906. Next, a boy named Nimrod Hunter Steele (1839-1861) was born. “Nim,” as he was called, died of typhoid fever he contracted in camp after the Battle of First Manassas while serving as a Confederate soldier. Philoma, or “Lomie” (1841-1925), was the third eldest daughter. As addressed in the article about the Dinges family, Lomie Steele Dinges, was the wife of Henry A. Dinges. They owned and lived in the log side of the Stone House duplex from 1867 to 1879. Lomie was followed by the two boys who later became the firm of Steele & Bro. Mager William Steele who was born 13 August 1842 was followed by Milton Boyd Steele, born 27 February 1845. “Milt,” as he was called, was followed by another brother named John who was born in 1848 and died as an infant in 1849. The last two children born were Sarah Eliza Steele (1851-1933) and John Magill Steele (1853-1936). John eventually went into business “merchandising,” partnering with his brother-in-law Henry Dinges. The firm of Steele & Dinges began in 1873 at the same location where Steele & Bro. opened their original store in the spring of 1869 on the southwest corner of Marlboro Road and Main Street.

Mager W. Steele and Milton B. Steele were sole proprietors and partners that made up the firm of Steele & Bro. They were both sons of Mager Steele, Sr. (1788-1863), and Eliza Kern Steele (1808-1882). Mager Steele Sr. was the son of Thomas Steel (1750-1834), an immigrant from Belfast, Ireland who came to America around 1765 and eventually settled southeast of Stephensburg in the area where Wise Mill Lane crosses Stephens Run. The first of the nine children born to Mager, Sr. and Eliza were girls. We know very little about Ann Margaret Steele (1836-1863) who may have been an invalid, and died during the Civil War a month after her father passed away. Inez Virginia Steele (1838-1912), the second oldest daughter, never married and was the author of Early Days and Methodism in Stephens City, Virginia, published originally in 1906. Next, a boy named Nimrod Hunter Steele (1839-1861) was born. “Nim,” as he was called, died of typhoid fever he contracted in camp after the Battle of First Manassas while serving as a Confederate soldier. Philoma, or “Lomie” (1841-1925), was the third eldest daughter. As addressed in the article about the Dinges family, Lomie Steele Dinges, was the wife of Henry A. Dinges. They owned and lived in the log side of the Stone House duplex from 1867 to 1879. Lomie was followed by the two boys who later became the firm of Steele & Bro. Mager William Steele who was born 13 August 1842 was followed by Milton Boyd Steele, born 27 February 1845. “Milt,” as he was called, was followed by another brother named John who was born in 1848 and died as an infant in 1849. The last two children born were Sarah Eliza Steele (1851-1933) and John Magill Steele (1853-1936). John eventually went into business “merchandising,” partnering with his brother-in-law Henry Dinges. The firm of Steele & Dinges began in 1873 at the same location where Steele & Bro. opened their original store in the spring of 1869 on the southwest corner of Marlboro Road and Main Street.

The Steele boys followed their father into the mercantile trade. A ledger book once belonging to Mager, Jr., now in our museum’s collection, shows that he was extending credit to a local customer as early as 28 July 1859 while he was still just 16 years old. This early ledger also reveals that Mager, Jr. was selling things like shoes, boots, tobacco, coffee pots, tea kettles, and turpentine in 1860 and 1861. At the same time his father, Mager, Sr., was experiencing setbacks. During those final years of his life before the Civil War, John M. Steele records how his father first lost a court judgment against him as a cosigner on a bond for a Frederick County Sheriff who had “defaulted in a large sum.” In turn, Mager, Sr. was then “left in the lurch by his partner” who failed to satisfy the court claim using notes of debt owed to the partnership. By the time of the Civil War, the Steele family was already suffering hard times.

The eventual success enjoyed by Mager, Jr. and his brother Milton as the firm of Steele & Bro. would have been difficult to predict during those devastating years. Both Mager, Jr. and Milton followed their late older brother Nim into the Confederate Army. Mager enlisted in the 48th Virginia Infantry near Berryville, Virginia on 1 November 1862. Prior to that he had served with the 51st Virginia Militia and participated in tearing up the railroad tracks at Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg. Milton enlisted in Company A of the 1st Virginia Cavalry on 1 September 1863. Prior to that, and shortly after the deaths of his father and oldest sister, Milton had served as a wagon driver attached to the 1st Virginia Cavalry during the Gettysburg Campaign. Both Mager, Jr. and Milton stayed with their respective units through the war until the surrender at Appomattox. They then returned to a local economy that was in ruins. We can glimpse into the business activities of Mager, Jr. in those post-war years by looking at the ledger mentioned above. The title page reads “Mager W. Steele’s Ledger Feb 1st 1866.” This date may indicate when Mager, Jr. officially went into business by himself, even though entries in this ledger show that he was extending credit to customers prior to the Civil War, and just after it in 1865.

In addition to Mager Jr.’s ledger book, we also have the diaries and memoirs of some of the Steele family members, including Milton’s post-Civil War era diaries. These diaries show that after the Civil War both Mager and Milton returned to Stephensburg to salvage what they could from the wreckage of the local economy. John M. Steele, Mager and Milton’s youngest brother, wrote the following in his memoir: “At the close of the war in the Spring of 1865, you might say that everything was desolation and almost ruin; all barns and out buildings had been torn down or burned, all fences burned or carried away, and people were put to their wits end to find some honest way to make a living.” Taking work that had formerly been done by slaves, Milton and his younger brother John spent one summer tending wheat and corn crops at Pleasant Green, the farm of ex-Confederate General James H. Carson. By the spring of 1866 Milton was hired part-time at the firm of John Allemong & Gervis F. Mayers. In his diary Milton noted on 1 April 1867 that he was commencing his second year of work for Allemong & Mayers at a salary of $200 a year. Little did Milton know that he was working in the same store that he would later own with his brother Mager. In the spring of 1868 Milton rented a farm while his youngest brother John undertook the contract of herding the cows on that farm. By this time Milton was also courting his future bride Altha Watson.

In addition to Mager Jr.’s ledger book, we also have the diaries and memoirs of some of the Steele family members, including Milton’s post-Civil War era diaries. These diaries show that after the Civil War both Mager and Milton returned to Stephensburg to salvage what they could from the wreckage of the local economy. John M. Steele, Mager and Milton’s youngest brother, wrote the following in his memoir: “At the close of the war in the Spring of 1865, you might say that everything was desolation and almost ruin; all barns and out buildings had been torn down or burned, all fences burned or carried away, and people were put to their wits end to find some honest way to make a living.” Taking work that had formerly been done by slaves, Milton and his younger brother John spent one summer tending wheat and corn crops at Pleasant Green, the farm of ex-Confederate General James H. Carson. By the spring of 1866 Milton was hired part-time at the firm of John Allemong & Gervis F. Mayers. In his diary Milton noted on 1 April 1867 that he was commencing his second year of work for Allemong & Mayers at a salary of $200 a year. Little did Milton know that he was working in the same store that he would later own with his brother Mager. In the spring of 1868 Milton rented a farm while his youngest brother John undertook the contract of herding the cows on that farm. By this time Milton was also courting his future bride Altha Watson.

Mager’s ledger book from this period after the War shows that he was extending credit to respected neighbors and family members, including his brother Milton. This ledger books shows that Mager was lending cash, as well as selling things like “segars,” canned oysters, sugar, coffee, tobacco, “dress goods,” buttons, and fabrics like cotton and calico. The relatively few entries in this ledger indicate that business was slow and that Mager was reluctant to extend credit outside of his immediate circle of family and friends. Mager apparently did not have a store from which to sell these things to the public. An entry in this ledger dated 15 February 1866 indicates that for the six months prior to that date he had been working as a clerk in the store of Robert H. Long for $30 a month. A similar entry in February of 1867 shows that he received another $180 for an additional six months of work at Long’s. By 1867 Mager was comfortable enough with his income to get married, and on 5 March of that year he wed Martha Jane Canter. One month after getting married Mager was able to purchase a house on the east side of Main Street near its intersection with Locust Street. The property had come on the market suddenly after its previous owner has defaulted on a deed of trust. John W. Ritenour purchased it and then immediately sold it to Mager for $55 more than he had paid for it. In the deed Ritenour states that he was selling the property to Mager “in behalf and for the benefit of his wife Martha Jane Steele.” On page 14 of Mager’s ledger he notes in the top margin that he moved into this new house on 9 May 1867.

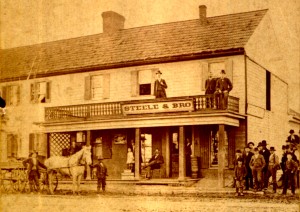

An article in the 22 October 1881 Stephens City Star stated: “The well known firm of Steele & Bro. was established in the spring of 1869.” At that time the railroad between Winchester and Strasburg was being built, and Newtown was going to benefit from that new line. On 22 March 1870 Milton married Altha Watson, and by June 1870 the railroad had started to run on a regular schedule. Steele & Bro. had opened their first store in the building on the southwest corner of Main Street and Marlboro Road on In Lot 31. The deeds for this property show that they were renting that building at that time but by 1872 they were doing well enough to purchase a property of their own. In that same year John Allemong, Milton’s old boss, passed away, and by the fall of 1872 Steele & Bro. had purchased Allemong’s house and store. Mager and Milton then moved up the street to their new location and left their old store on In Lot 31 to their younger brother John M. Steele and their brother-in-law Henry A. Dinges. Milton and Altha, who had been living in the old Steele school house at 5190 Main Street, on the north end of the town, moved into the old Allemong house on In Lot 26 next to the new store. This home located at 5357 Main Street is called The Steele House today in honor of Milton B. Steele and is the location of the house that George Cabbage moved into after he sold the Stone House in 1767.

Earlier that year, in January 1872, Mager and Milton had purchased the stone side of the Stone House. There is no evidence that they intended to use it as a store. Both men already had houses, so it is unlikely that either of them considered it as a future residence. The best clue we have about the way this property was being used at that time comes from Mager’s ledger. On Page 18 there is an account for “C.H. & I.B. Guard” who were paying $1.50 per month rent on a house that they had moved into back in November of 1871. Later on page 20 and 21 of this ledger book Mager records that in 1875 Enoch Jenkins, an African American blacksmith, and a man named Aaron Thomas were each renting separate houses at $2.00 and $1.50 per month respectively. It is also clear that the stone side of the Stone House was not the only property the brothers were leasing out. In September of 1872 (about eight months after purchasing the stone side of the Stone House) Mager and Milton purchased, a 118-acre farm with a house called the “Cross Roads Tract” for $1,180 about a mile east of town.

The ledger does not identify the location of the properties that were rented. “C.H. & I.B. Guard,” who were paying $1.50 per month on a house they had moved into back in November of 1871, were most likely Charles H. Guard (1840-1896) and his older brother John B. Guard (1839-1913). (Mager used the old custom of substituting the initial “I” for the letter “J” in his ledger book.) County and Federal census records show that both of these Guard brothers were married at that time and working as carpenters. Their mother was Emily Shryock Guard, the oldest daughter of Frederick Shryock and sister to Charles and Jacob Shryock, the previous owners of the stone side of the Stone House. This Shryock family connection, combined with their dates of tenancy recorded in Mager’s ledger, strongly point to Charles and John being the tenants in the stone side of the Stone House when Mager and Milton purchased the property. In other words, the Guard brothers, who were already renting the property from their uncle, began to pay rent to Steele & Bro. in January 1872. It is very likely that Charles and John Guard were leasing the property as a winter/off-season shop for their carpentry business. By April of 1872 Mager’s ledger records that “Edd Shryock” had started to pay the rent on the house. Perhaps the spring weather and the return of the building season brought an end to the Guard brothers’ tenancy. In any case, the account ends on 15 May 1872 with Edd Shryock paying rent for one more month. It is possible that after that time the account was kept in another Steele & Bro. ledger book.

Mager’s ledger also recorded accounts for Enoch Jenkins, an African-American blacksmith, and a man named Aaron Thomas. The entries for Jenkins and Thomas both start on 20 April 1875. Enoch Jenkins’ account states that his lease was for one year at $2.00 per month. Aaron Thomas’ account states that he rented another property at $1.50 per month. It is difficult to know for sure which property was being rented by Jenkins. In the 1850 census Enoch and his younger brother Levi were both free blacks working as blacksmiths for another blacksmith named George Guard, the father of Charles and John Guard. During the Civil War Levi joined the Union cause and was captured after General Milroy’s defeat at Winchester on 15 June 1863. Eight days later Levi was being marched south through Newtown to be enslaved by his Confederate captors. This fate was apparently too much for Levi to endure. As he passed the old home of William McLeod (where 5331 Main Street is today) he broke free, ran, and jumped into the well on that property. After his brother’s suicide, Enoch continued to live and work as a blacksmith in the area. It is possible that his relationship with the Guard family is an indication that he was the one who rented the Stone House from April 1875 through July 1877. On the other hand, Aaron Thomas only rented his house from Steele & Bro. for three months. It is likely that this Aaron Thomas was also a member of the African-American community. The 1880 Census lists a 53-year-old African-American “laborer” named Aaron Thomas married to a Ruth Thomas. It is likely that this Aaron Thomas is the same man who rented from Steele & Bro. in 1875. It is also possible that the house Thomas rented was the one on the “Cross Roads Tract” near the African-American suburb known by the white community as “Freetown” and called “Crossroads” by the black community.

We have yet to find any other surviving records that would shed any more light on the tenants who rented the stone side of the Stone House during this period. It is possible that Steele & Bro. also used it as employee housing. In any case, the Steele’s business continued to thrive until tragedy struck on 3 February 1884, when Milton died of meningitis. After Milton’s death, Mager continued to operate the business as “Steele & Bro.” until he passed away in on 26 August 1900 after a long illness. Just prior to his death the stone side of the property was sold to Katie Mae Lemley Parker.